CASTING

FORWARD

PUBLISHED JUNE 1, 2022

In April 2021, several Ms. Mayhem reporters undertook an ambitious project. They wanted to learn how women were evolving the sport of fly fishing.

The team initially approached the project through three main lenses: gear, safety, and conservation and education. Since then, they’ve added a fourth focus examining the lack of visibility and representation for women of color and other marginalized groups. They spoke with company founders making equipment more accessible; heard women’s experiences of safety concerns on and off the water; and discovered how women are shaping conservation efforts.

Our reporters spent hours in the car traveling across Colorado, conducted interviews over Zoom, and even made it out to Chattanooga, Tennessee, for a weekend to bring these valuable stories to you.

The project consists of four multimedia stories and five films.

“I fell into the water, and water started coming down into my waders,” said Lisa Le, who has been fly fishing since 2017 and is a director at large with Colorado Trout Unlimited. “Luckily, I wasn’t in deep water so I was able to get out of the water pretty quickly. But it does affect your safety. If I didn’t have my pack on, I could have drowned.”

Le’s problem was that her waders didn’t fit her properly. The waist pack cinched only so much on her, leaving the waders loose. Had she been in a deeper channel, water flooding into her waders could have dragged her beneath the surface and kept her there.

Whether it’s a belt, the size of the booties, length of the pant leg or width of the waist, ill-fitting gear is a problem that is frustratingly common to a vast majority of women. Le said that the issue doesn’t just affect women with smaller builds, like her. It affects women of all sizes. Larger people run the risk of ripping their waders if they bend down to pick something up, letting water in and carrying them downstream.

This problem is caused by something deceptively simple: manufacturers don’t incorporate the wide range of possible body types into their designs.

“It really comes down to we’re still using standard sizing, you know, from runway models. You know, they don’t work. They’re not right. I actually created my own sizing system based on research. It’s not—you can’t compare it to any chart on the market,” said Kim Ranalla. She owns Miss Mayfly, a company dedicated to designing waders for women.

Even the type of fabric can betray the sort of design biases built into practices used to make waders. Men don’t sway a lot, Rannalla said. They’re straight and stiff and therefore can wear a stiff fabric. Because of that, she said designers don’t need to worry a lot about how it fits them.

“But, women have curves and we have sway. So now, we need a fabric that moves. It’s that simple. You need a fabric that can move with a woman’s body,” she said.

Ranalla’s interest in fly fishing was born when the sport became a type of therapy after suffering a combination of spinal injuries and muscle tears at her job as a group home counselor. Although she had grown up spinner fishing, she had never fly fished before. At her friend’s suggestion, she entered the water.

It was also her first exposure to the problem with gear sizing that most women face. Her first time wading, she wore a man’s wader that was too long for her. She was determined to find something that fit her, but she found it to be an endless task. Whatever Ranalla tried either ballooned whenever she sat down, was too big, or constrained her movement. Believing shopping for her daughter would be easier since she was smaller, Ranalla looked for waders that fit a size 10 foot. What she found ended up being massive on her daughter anyway.

Those experiences inspired her to develop her own waders. Two years of development later, she had her first product and Miss Mayfly was born.

Ranalla studied the issue day and night for a year. She went through reviews for other products, taking note of each instance where the wader didn’t fit, was too heavy or stiff. Complaints about giant booties needing to be rolled and stuffed into a boot abounded. “I saw that most women, a lot of women, the majority of women could not fit in a wader comfortably,” she said.

In the course of her research, Ranalla found that almost 70% of women are size 14 or above. Most manufacturers did not, and still don’t, make waders larger than women’s size 14, meaning that nearly two-thirds of women had to use men’s gear since nothing else was available.

That misfit that many women have to deal with carries physical consequences. Aside from the safety issues, ill-fitting and stiff clothing imparts a movement penalty. On the river, that translates to fighting with one’s gear just to move. It’s easier for exhaustion to set in.

A key discovery Ranalla made while designing her waders was that when other outdoor apparel manufacturers design products for women, they actually base all their design assumptions around that of a male body. Not only does this produce the wrong measurements and sizing in product design, it also limits the scope of bodies that these waders could fit. The problem is deeply ingrained within the mindset that designers use when making waders. When Ranalla hired a female designer to work on the sizing chart for Miss Mayfly, she received measurements that were identical to that of her competitors.

So Ranalla decided to start from scratch. She poured all her time into learning design, wrapping herself up in jackets and coats to see how they fit and studied how each body part grew and worked inside a garment.

“I didn’t have all the fancy designer equipment to use,” she said. “So I went through that whole process and the more I studied, the more I said, ‘Okay, well, this isn’t good enough, this isn’t good enough. I have to fit this person. I can’t forget about this person.”

Penny Mabie is one of the almost 70% of women that most manufacturers don’t design for. She’s been fly fishing since the ’90s and has seen the sport change over time. Although she has seen a lot of positive developments since then, she still sees room for improvement.

“It makes me a little angry, makes me a little frustrated,” she said. “Because it feels a little hypocritical that companies are saying we want more diversity on the water, but they’re not doing the things that support more diversity on the water.“

Mabie is a plus-size woman who often ends up buying men’s apparel for her fishing trips because what’s available to her in women’s sizes doesn’t fit her body type. Not only does she want more options that can fit her, but that also fit her personality. She said that, as a woman of size, she can name three major companies that don’t make gear that fits someone like her. Because of that, she doesn’t even bother looking at their catalogs anymore. For the longest time, she stuck to neoprene waders because any other option had booties that, in her words, were 6 miles too big.

Once when Mabie was out on the water, she received several compliments from the women she was fishing with. Her choice of jacket that day was a thin men’s khaki jacket. The color was singled out for praise, with some of the women exclaiming that they had been unable to find that color in the store. Unlike men, most women’s gear is colored in stereotypically “female” colors. There’s a phrase for this in the broader outdoor industry: shrink it and pink it.

The phenomenon refers to the practice where manufacturers or brands want to adapt a product for women that was previously made for men. But instead of taking the design standpoint of, “how can we make this meet a woman’s needs,” they take the lazy way out with their design.

“So instead of really digging into the mechanics, or the performance, or the whys behind the gear that women might want, they simply changed the gear to be smaller or changed the color to meet the supposed needs of women,” said April Archer, owner of SaraBella Fishing, a company making custom rods for both men and women. Ergonomics is one of the key things she’s concerned with when she designs her rods, along with how the rod reflects the user’s personality.

Many women find the “shrink it and pink it” mentality off-putting, especially if they’re forced to wear colors or items that don’t reflect their personality. The fact that pink gear exists isn’t the problem itself but rather the lack of choice for a broad spectrum of preferences. Being forced to go fishing in something that doesn’t represent the wearer’s personality can be a blow to their self-confidence. This can have an impact on their ability to perform out on the water or on their desire to go fishing in the first place.

“I love hearing the stories when people say, I feel like I catch more fish, or, I feel like I’m a little more confident because I didn’t have to settle for gear that wasn’t built for me or designed for me,” Archer said. “So when people say that they feel that their gear speaks to them or even helps their performance, it’s incredible.”

One major theme emerged after talking to these women. Currently, a lot of the inclusivity work being done by some of the major players in the industry amounts to little more than lip service. More work remains to make fly fishing truly inclusive. To accomplish that, many women are tackling the problems they see within the industry on their own. They’re questioning old assumptions about how clothing and gear are made. They’re creating the change they want to see on the water, and chipping away at the obstacles preventing true inclusivity.

Filming by Polina Saran and Esteban Fernandez

Anglers perform several basic safety checks anytime they step out onto the water: check the flows, watch for wildlife, carry at least the minimum amount of first aid and wear the proper gear.

But as a woman, things are often more complicated. As with any other aspect of our lives, outdoor recreation comes with the threat of being harassed, assaulted or even killed. The anxiety of being the next name plastered across national news sits in the back of our minds—Mollie Tibbetts, Crystal Michelle Turner and Kylen Carrol Schulte, Meredith Emerson, Julianne Williams and Laura Winans.

“We need to be conscious and mindful of our surroundings and animals and weather and all sorts of things that you have to just be cautious of in the outdoors,” said Hannah Kramer, a special education teacher in Denver and fly fishing influencer. “But unfortunately, on top of that, what we’re working with is, [that] being a woman and fishing alone can come with its own series of issues.”

Kramer said fishing alone in a busy spot, like Deckers or Cheesman Canyon, poses few safety concerns. Other anglers—who are mostly men, she adds—may come up to chat or poach an occupied spot on the river. But what’s often more frightening, Kramer said, is fishing in a more deserted area or during a slower time of day when there are only one or two other people. She said she’s had a few experiences that left her feeling uneasy, even causing her to stop fishing for the day.

One example involves a man who continuously harasses her “since the moment” she first posted online about fishing. He sends rude messages, leaves crass comments and has created group chats with other men to talk about her.

“I was fishing by myself one day, and I noticed that he was on the water. I just chose to leave. I just didn’t want to have to deal with having to constantly be on guard. I didn’t want to be in a [situation that], one, could potentially be dangerous, or two, this guy had an opportunity to take pictures of me to share with his group chat and post on social media,” Kramer said. “I just didn’t want to have to be so hyper-focused on how I was acting, because there was the potential for this bully to be documenting it and harassing me, so I just left.”

And Kramer isn’t alone in her experiences. In 2016, the U.S. Department of the Interior conducted an investigative report, zeroing in on the Grand Canyon River District in response to a letter of complaint from 13 former and current National Park Service employees. They claimed to have experienced or witnessed “discrimination, retaliation and a sexually hostile work environment.”

The investigation and subsequent report confirmed these claims and more: sexual propositioning, inappropriate touching and verbal harassment ran rampant. Sparked by this realization, several outlets and organizations took it upon themselves to conduct further surveys, most of which focused on specific outdoor industries like running, rafting and climbing. They found that conservation organizations and outdoor sectors across the board were plagued with these problems.

Seeing these results, Outside Magazine conducted a survey of its readers in 2018, casting a wider net to the outdoor industry and participants in outdoor sports in general. Of the 4,193 mixed-gender respondents, a whopping 70% said they had been harassed themselves, with catcalling or unwanted following making up the most common cases.

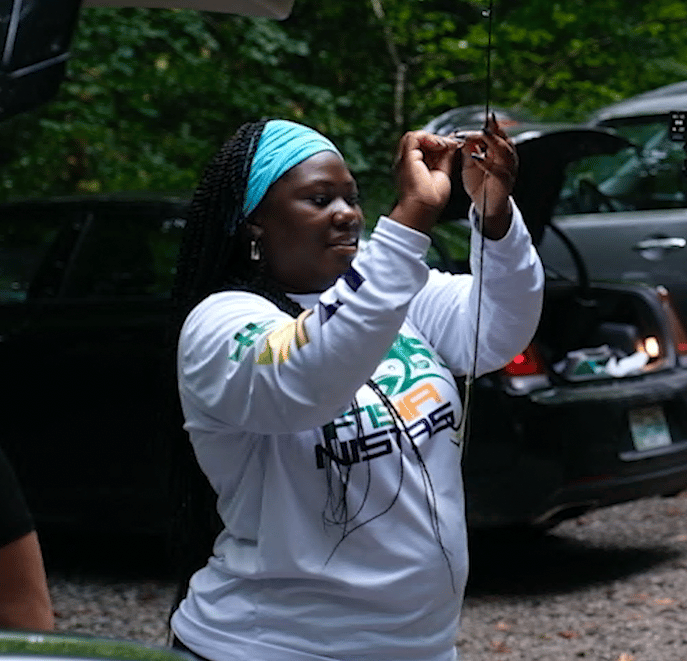

These safety concerns balloon for women of color and LGBTQ+ folks, who lack representation, access and safety in the world of outdoor recreation. Fishanistas Executive Director Jeanine Blair can attest to that reality firsthand and said that navigating the white-dominant sport of fly fishing is often uncomfortable.

“Just being a Black woman, being in this industry and walking to the water, our safety measures are three times what someone else’s are,” Blair said. “We can’t go to remote areas unless we have, truly—and it’s just the truth—unless we have somebody white with us. And a lot of times, that’s not even a security, but it kind of gets us through being Black in America and in this fly fishing industry.”

Passing knowledge to the next generation of Black anglers is a safety issue for Blair as well, who said it’s not as simple as just taking her kids out on the river for the day as many white parents do.

“We’re trying to build this community where I can teach my kids; I can teach somebody else’s kids; I can teach these kids that do not have an opportunity to learn. When it comes to fly fishing, I have to make sure that these kids are safe. I have to take them to well-lit areas [and] make sure that it’s a welcoming part of whatever place that we’re going—The things that white people or any other race of people don’t have to worry about, we still have to worry about.”

Penny Mabie, a queer woman who traveled around the country for the better part of 2021 to fly fish, said she felt inclined to remove certain stickers from her car—including a rainbow flag and a Human Rights Campaign logo—before setting out.

“When I told [a guide] that I took my rainbow flag off, he said, ‘Why?’ And I said, ‘Because I don’t know that I’ll be safe everywhere I go.’ I mean, that tells people something about me,” Mabie said.

While harassment can and does happen on the river, it’s more pervasive online. Women fly fishing influencers face a constant barrage of messages and comments on social media, mostly from men criticizing their bodies, looks or fishing skills.

“I have seen some people on [women’s] videos and pictures just go in on people’s appearances and say, ‘You look too pretty to be at the river.’ And I want to know, what are we supposed to look like?” asked angler Abi Weiss.

The online hostility toward women in the fly fishing world surged after Orvis, the country’s oldest fly fishing outfitter, released a video on YouTube announcing their 50/50 On The Water campaign in 2018. The campaign was an effort to increase gender parity in the sport. Four years later, the video has garnered 465,000 views and 408 comments, the majority of which accuse the company of pandering to feminists or starting a “war between the sexes.” The commenters, mostly men, insist that barriers for women to enter the sport are simply imaginary.

“The comments on the Orvis 50/50 video were very much expected; they weren’t shocking,” Weiss said. “But it’s annoying that that video was legitimately purposed to talk about inequalities and then males come in and literally say, ‘Women don’t need any additional representation.’ It made me feel frustrated that we still have to deal with that.”

But some of the comments carry far more venom. One commenter in particular references the Men Go Their Own Way movement, a mostly online, misogynist group that advocates for men to separate themselves from women and a society that they believe has been poisoned by feminism.

That kind of malice is what drove Trouts Fly Fishing Director of Education and guide Courtney Despos off social media for a period of time. Despos said when she first started guiding, she would receive messages and comments from men asking her to take them out on the river in a “sarcastic, mean, undercutting, condescending way.” But the influx of responses she received quickly became more vicious.

“I literally got death threats,” Despos said. “I got people messaging me, telling me I should commit suicide. I had people telling me that my son would be better off if I wasn’t on this Earth. I went through hell and back for a good year, year-and-a-half. I was definitely targeted hard.”

But it doesn’t take something as extreme as death threats to minimize women’s contributions to fly fishing. Many women, like Kramer, monitor the public comments they receive on their posts to protect themselves and other women from the harm they can cause. When she first started going for sponsorship deals, Kramer posted a photo of herself with a fish. That photo was screenshotted by a man—who Kramer didn’t name—and reshared to a Facebook group called Renegades on the Fly. He insinuated she had STDs and was “selling herself” for fishing gear.

“[Other] things have happened similar to that,” Kramer said. “Typically, it’s men who will send me messages or leave comments on photos that will accuse me of not knowing what I’m doing, having somebody else catch my fish or having no skill and that I just get offers for sponsorships or travel opportunities because of the way I look.”

Kramer also shared screenshots of comments, left on her social media pages or in Facebook fishing groups, with Ms. Mayhem. One user also made comments about her breasts, saying, “She blocked me…I guess I made too many jokes about getting free shit if you had big tits. Notice I said big and not nice.” Others insulted her fly-tying skills, with one deactivated user commenting, “You suck at tying…why are you promoting yourself on Instagram relative to fly fishing? Why the hell do you call yourself a public figure?”

Kramer often posts these responses in her Instagram story, blocking out the names of the offenders so as not to become a bully herself.

“The reason I post those things is to bring awareness to individuals and white cis[gender] men, mostly, who have no idea that this is happening to women all the time,” Kramer said. “I’m going to call it out because simply being complacent has not worked. We have all tried to be complacent, and it’s done nothing. I think it’s really time that everybody steps up and helps each other and stands up for themselves.”

One Instagram user, @icbt0722, almost exclusively bashes women anglers by posting screenshots of photos from their personal pages. Photos of Kramer and other well-known women in the industry, like Tessa Shetter and Shyanne Orvis, are paired with captions insulting their clothes, bodies, hair and makeup accompanied by hashtags like #girlsdontfish and #dumbbitches. The account hasn’t posted for over a year but maintains almost 200 followers.

Over the last decade or so, the fly fishing industry has made significant strides in helping women feel more welcome on the water. But those strides aren’t necessarily intersectional with BIPOC or LGBTQ+ identities, nor will they ever be truly effective until hateful rhetoric becomes intolerable to those with the power.

“I think there’s so much road left to travel before fly fishing becomes equitable for women,” Kramer said. “I think that there’s less road than there was five years ago, but I wouldn’t say that we’re even halfway there. I think the right things are being done, but I think there’s more that needs to be done. My hope is that if we all educate ourselves, we work together, we just treat each other like humans, then maybe that road becomes slightly smaller.”

Filming by Polina Saran and Esteban Fernandez

SCOPE OF INCLUSION

However, even as women struggle to be included at all levels in the sport, their front is not a united one. Women are balkanized into different groups, riven by the same divisions that reflect the larger fault lines characteristic of American society.

“I think white women have always had a space, and folks of color, especially women of color, have never had our own space,” said Erica Nelson. “There are benefits in affinity spaces where, you know, women can feel welcomed and celebrated in their own groups.”

Nelson is the first Indigenous woman fly fishing guide in Colorado, out of Willowfly Anglers in Almont. She resides on the ancestral land of the Ute, now partially known as Crested Butte. When she’s not fishing, she consults on diversity, equity and inclusion issues through her firm, REAL Consulting. She also hosts a podcast called the Awkward Angler and is an ambassador for Brown Folks Fishing. The group is dedicated to holding representational space for people of color in the fishing industry.

Whiteness and the effort to dismantle it is one of Nelson’s primary preoccupations. She is critical of white women and the paradoxical place they hold as both oppressors and the oppressed. One of the things she points out is how a lot of current activism carves out spaces for white women within the fishing industry but simultaneously excludes women of color.

There is historical precedence for that perspective. The suffragette movement in the 19th century split into two factions. Those who supported the 15th amendment—which protected the right to vote regardless of race—and those who did not. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, two leading figures of the suffragette movement, joined the side opposed to the 15th amendment. At the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, no Black women were invited. In the 1920s, Black women and women of color oppressed by racist voting laws reached out to the leading suffrage organizations of the time only to be ignored. Carrie Chapman Catt, a leading suffragette in 1918, dangled the promise of securing white supremacy in the south to North Carolina Congressman Edwin Webb. She argued that white women and white men could vote together to keep Black people, and Black women, oppressed. Barriers to voting such as jim crow laws kept Black women from voting long after white women received the right to vote.

Nelson said that white women have both been silenced and have benefited from white privilege. Because of this relative privilege, white women can carry attitudes that cause harm, including within the fly fishing space.

“When I call that out, they revert back to their feelings and their emotions and try to weaponize that,” she said. “Really use that to leverage other white women to find comfort, where I’m looked at as the oppressor. I’m getting really tired of that narrative.”

At its core, oppression is ultimately about who deserves to belong and who doesn’t. Howsoever that question is answered carries knock-on effects on how a society treats those it deems unworthy of belonging. As such, there are multiple dimensions to how oppression manifests. Historically in the U.S., racism was overt but in less than a century has become covert, subtle and insidious. It can even be something as simple as who is featured in advertisements.

Jeanine Blair is the executive director of Fishanistas, an organization that works to inspire more women and girls to fish. She pointed out that the magazines and advertisements that revolve around the sport usually feature slender white women with flowing hair who look nothing like her. It’s gut-wrenching to see a body like hers be left out of all those magazines, she said.

At first, Blair was excited when Orvis, the country’s oldest fly fishing outfitter, launched a campaign to get more women on the water. But she soon became demoralized.

“The way I feel about 50/50 On the Water is, Orvis, what women are you talking about?” she said. “Please tell me, what women? Orvis, I do not see women who look like me. Being a Black woman in the industry, we’re the last on the food chain.”

The campaign was supposed to offer a way for new anglers to take classes on casting and fly tying. Blair reached out to the company to get someone to come to teach her group, but no one returned her calls. She felt ignored.

“It was gut-wrenching to know that nobody—I felt nobody wanted me on their waters. Nobody wanted me to participate in this elitist sport,” Blair said.

That feeling of alienation is compounded by the physical risks that Black people face just by existing in America. As a Black woman, Blair said she takes three times the safety measures that someone who is not Black takes out on the water. That feeling of safety is elusive, even when with a white friend. Carrying a gun is something she’s considered.

“But once again, here we’ve got that stereotype. Black people shoot people; Black people are this—No! Black people are trying to protect themselves,” she said. “And until you walk a day in a Black man or Black woman’s shoe, don’t say a word. We are trying to survive.”

Circe Tsui is one of the lucky ones to have met mostly wonderful people when she goes fly fishing. But sometimes, she encounters moments that make her question why someone is doubting her experience or skills.

“I do feel like once in a while, I’ll be asking a question in a shop, and I got dismissed because they feel like I didn’t know what I was talking about,” she said. “You know, it could be a combination of race and gender, right? They could be looking at me like a little Asian lady.”

She was even once quoted one price for an item at a shop while someone else got a different price.

Tsui also pointed out that companies failing to be inclusive in their business practices carries real costs for them. She said that even if a company is trying to attract customers like her with their marketing, she won’t buy anything from them if they don’t back it up by making products that she can fit into. If they don’t have the right stuff, then it doesn’t matter what they say.

What Tsui discussed about a company’s marketing versus what is actually available strikes at a deeper core. With talk of diversity, equity and inclusion—also referred to as DEI—all the rage among public relations and marketing professionals, the issue of whether those are hollow words becomes an important one.

“Everybody is talking. It’s another DEI after DEI meeting, but in these meetings, what is actually happening?” Blair asked. “Where is the action, where is the work?”

People often ask Nelson how they can do the work necessary for true social justice. She has a short answer for them: Google. That answer might be brusque, but it’s born of years of experience with people demanding easy answers and no effort on their part.

Her favorite analogy is that of a new angler approaching an experienced teaching guide for help. She said it’s easy to quickly spot who is actually interested in learning the sport versus someone who is only looking for a way to kill an afternoon.

The angler who is actually interested will show up prepared with some research they did on their own. Maybe they looked up the best locations, what the weather would be like, familiarized themselves with how to tie flies and learned the terminology. When they show up with the guide, they’ll have a better idea of what kinds of questions to ask. Maybe they ask what type of fly the guide recommends to match the hatch. They show genuine interest.

Now, compare that to a tourist. They show up and expect the teacher to do all the work for them. They demand that the guide tell them when to cast, or expect the equipment to be prepared and ready for them, with no effort or preparation on their part. They have no real interest in the sport, they just want a throwaway experience they can brag to their friends about. They want to benefit from someone else’s labor.

Apply that analogy to social justice, and the distinction between those two types of people takes on higher stakes. One person is actually working toward dismantling systems of oppression, even if it’s on a small scale. The other person just wants to give the right impression without putting anything meaningful behind it.

And when someone actually does the work, the impact is evident. Despondent after being ignored by Orvis for two years, Blair said that Miss Mayfly reached out to her.

“Kim Ranalla, the founder of Miss Mayfly, she just out of the blue called me one day and said, ‘Could I talk to you about what it’s like and your challenges and fly fishing?” Blair said. “I broke down, I mean, literally broke down into tears because it was something that meant so much to me.”

Blair credits Ranalla for helping her learn about fly fishing, she’s even an ambassador for Miss Mayfly. Another company Blair credits with putting in actual effort to the work is Mercury Marine, a marine engine company. She said they reached out to Fishanistas and asked how best they could support the group. Blair said showing up is a game-changer, and appreciated how the company was willing to have the difficult kinds of organizations that other companies avoid. They’ve even done town halls with Black people.

Blair’s goal is to get more women who look like her to start fly fishing and hopes she will someday see a Black woman on the cover of magazines like Trout Unlimited. There’s money behind working toward true inclusion, too. Blair said that Black people spend about $8.5 billion in the fishing industry. The only question is, where are they going to spend it?

There’s always going to be an evolution, Nelson said. Organizations that are resistant to change are going to be left behind and eventually dismantled. Younger generations will say that they can do this better, be more inclusive. Nelson already sees more and more people who look like her fishing, which makes her feel safe and seen. She also says that marginalized people talk amongst themselves, and they know who is being sneaky and who is actually putting in the work.

“There’s a lot of power in representation, also a lot of power in doing it authentically,” she said. “I think organizations need to be aware of tokenization versus representation and doing it well. I think that’s going to be extremely important.”

Filming by Polina Saran and Esteban Fernandez

On Dec. 30, 2021, Earth Lab Analytics Hub Director and fire scientist Natasha Stavros watched as the Marshall Fire raged through her hometown.

By the time the fire was 100% contained on Jan. 3, 2022, entire suburban neighborhoods in Superior and Louisville were leveled. It’s now considered the smallest yet most destructive fire in Colorado history, with over 1,100 structures damaged or destroyed.

“I was sitting on my couch, and I looked out my window in the direction of where [the fire] was located, and I did see a big plume and my immediate thought was like, this is really bad because we had had wind with gusts up to 105 to 120 miles per hour,” Stavros told Axios reporter Niala Boodhoo. “This is actually the first time that in my over 10 years experience I have ever felt comfortable saying that this is a climate fire.”

As the severity and frequency of weather patterns exacerbated by climate change increase, so do other warning signs. Infectious diseases spread rapidly across the globe as temperatures hit “Goldilocks zones” for disease-spreading pests like mosquitoes. One-third of all animal and plant species could face extinction by 2070, largely due to rising annual temperatures. The number of flash-flood warnings in Colorado in 2021 more than doubled the 10-year average.

Society at large is seeing firsthand what climate scientists have been sounding the alarm about for decades.

“We can’t survive as a species without natural landscapes,” said Kara Armano, a co-founder of Artemis. “That’s pretty much the overarching concept of it to me. If we don’t protect our landscapes, we don’t have clean drinking water. And if we don’t have clean drinking water, we don’t survive.”

The continued survival of all of Earth’s inhabitants relies on taking action now. As with other social movements, the impacts can be more effective when women take the lead, according to Erica Chenoweth, a professor of political science at Harvard. In Chenoweth’s research published in 2019, she partially credited this success to women’s employment of nonviolent protest tactics. She also pointed to social movements that center women’s voices, which attracts more women supporters, and creates a larger group of boots on the ground.

And when it comes to the fight for our planet, there’s evidence that women are slightly more likely to be concerned about the environment and hold stronger pro-climate opinions and beliefs.

“Women tend to really connect to a place really quickly, not necessarily compared to men, but it’s just something that I’ve observed taking women into the outdoors,” Armano said. “They just really understand how the whole ecosystem comes together, how it all has to work and be one to be a healthy, viable place. And not only that, but women are really great at talking to one another.”

Women have been at the forefront of most major social movements throughout U.S. history—particularly women of color, who were the unsung heroes of the suffrage movement. They combatted sex discrimination, ignited the fight for LGBTQ+ rights through the Stonewall riots and brought the Black Lives Matter movement to a global scale. Former videographer for Colorado Parks and Wildlife and co-founder of Inclusive Guides, Crystal Egli, said that women of color often have to step up to the plate.

“You always hear of women and women of color on the front lines—they’re the ones that show up in large numbers to community events, community organizing,” Egli said. “They are the glue that holds communities together often. It may have started out as assigned gender roles in the past, but honestly, I love being at the table. But at the end of the day, the people with the power and the authority and the privilege are the ones who can change those laws about the people who don’t. And so that’s why it is vital to have people with the most power in these rooms, in these spaces, but they just don’t show up. We do.”

And it’s essential they keep showing up. The climate crisis will disproportionately impact women, BIPOC, LGBTQ+ folks and other marginalized communities, according to United Nations Women, predominantly due to gender inequity in developing nations. Centering those voices now could help ensure a more equitable and sustainable future. But how? For many conservation organizations like Artemis and Brown Folks Fishing, the answer is clear: Get these people to enjoy the great outdoors.

“We all know that people are going to advocate more readily and heartily for places that they know the best,” Amaro said. “So when women are out on those landscapes exploring and adventuring and checking those places out—whether it’s hunting, fishing, hiking, whatever it might be—they’re really developing those connections and understanding what’s going on in their backyard and then able to act and advocate on any issues that might be affecting those lands.”

Conservation has been a traditionally white and male-dominated space that calls to mind the likes of Theodore Roosevelt, John James Audubon and John Muir. Many of these environmentalists held racist and misogynist views, which have influenced global conservation practices. Roosevelt’s penchant for big game hunting perpetuated the myth that wealthy hunters pay for wildlife conservation in Africa. Audubon benefited from information and specimens gathered by Black men he enslaved and Indigenous people. Many national parks and public lands set aside for conservation efforts reside on the ancestral homelands of Native peoples, who the U.S. government committed genocide against.

This history makes people like Erica Nelson, a fly fishing guide at Willowfly Anglers, Brown Folks Fishing Ambassador and host of the Awkward Angler podcast reluctant to continue using the term. While it is paramount we continue to protect natural waterways and land, Nelson said, doing so is about taking personal responsibility for how one chooses to recreate.

“Within our society—especially in the outdoor space and the outdoor industry—we have conservation that’s pretty much led by white organizations,” Nelson said. “We’re missing the historical context, which is we actually stole this land from Indigenous folks and removed them from this area—attempted genocide. Now we want to continue to protect it and we’re excluding the entire Indigenous community that has been stewarding this land for many, many years prior to colonization. I think conservation kind of needs to be looked at more deeply within how it operates under white supremacy.”

As outdoor sports and the conservation movement become more diverse, the next generation is seeing themselves in these spaces. Activists like Pattie Gonia, Rue Mapp, Teresa Baker and Patricia Nguyen work toward conservation efforts while making the outdoors safe for marginalized folks. Programs like The Mayfly Project and STREAM Girls—a partnership between Girl Scouts and Trout Unlimited—aim to get more youth out on the water.

Barbara Luneau, director of STREAM Girls for Colorado Trout Unlimited said education is one of four ways the organization achieves its vision of protecting, conserving and restoring cold-water fisheries and their watersheds.

“Our mission in education is to basically inspire the next generation of river stewards,” Luneau said. “We want to connect kids to the environment. We want to connect kids to watersheds and through that, expose them to a sport like angling that can be a lifetime connection to these places.”

The program utilizes fly fishing to introduce young girls to the STEM fields by teaching them about water flows, river ecosystems and conservation science. According to Leslie Shannon, a professor of engineering sciences at Simon Fraser University, girls are more likely to pursue a career in STEM when they can see why it’s beneficial. People, in general, are also more inclined to enter a field if they have role models who look like them. As the need for more effective, collective action against climate change is upon us, it is imperative that more women and marginalized people join STEM careers.

“I think the sky’s the limit,” Armano said. “More and more women are becoming visible in these spaces, holding elected positions, holding places that have determining factors on how landscapes are managed. I think that’s only going to increase over the years. The more women we see doing it, the more confidence we’ll get to maybe say, ‘Hey, we could do that too,’ and we could even maybe push it to the next level.”

Filming by Polina Saran,Ali Mai and Esteban Fernandez

Tell us Your Fly Fishing Story!

Return to Ms. Mayhem site

SUBSCRIBE

Become a Member

CLASSIFIEDS

Advertise With Us