The Sand Creek Massacre site isn’t Colorado’s most visited national park, yet many believe it is a place that draws a vector from Colorado’s past to its yet undecided future.

“When I was growing up, I would see old people sit and they would cry,” said Fred Mosqueda, the Arapaho representative for the Sand Creek Massacre site. “We would ask why and [our parents] would say ‘don’t talk about it, because they might come back.’”

Three things remain indelible in the mind on the drive from Lamar, Colorado to the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site.

First, the unrelenting gusts that shake the sparse trees, and at times are strong enough to rattle panels on a car.

Second, the sign leading out of town that proclaims the significant victories of the Lamar High School Savages. The name has been a point of contention in recent years, but as it stands, a caricature of a Native warrior looks out over the plains.

Third, just before arriving at the site, is the small town of Chivington. The town would be negligible if it weren’t for its name and the name of its church, “Friends of Chivington.” The Cheyenne and Arapaho have disputed over whether or not to change the name. Some say the name of the man who massacred their people is being honored; some say the town points to a racist history beyond one man.

For now, the name remains. As you leave it behind and arrive at the site sagebrush reigns king save for a few trees lining the dry creek bed. Despite the luring shade, guests, per the tribe’s request, must stand on a bluff above the creek.

A Retelling of History

In 2007, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site opened to the public through a conjoined effort with state, federal and tribal governments.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho directed every step of curating the site, down to the topics park rangers should cover, the information on signs and the spaces that guests can access.

One precise specification was that non-tribal members could not visit the creek bed. It was there that the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho were slaughtered and there that their remnants reside.

Informative signs share bits of history in the bluff above the creek. Despite collaborative curation, vestiges of a fractured past make themselves known throughout the area.

A designated repatriation site is marked a few steps away from the bluff. Interpretive Ranger Jessica Mason explained it as a place for descendants of American cavalry-men to return items and body parts taken during the massacre.

Mason attempts to help visitors unravel the tangled web of history that allowed for the massacre to be misunderstood as a battle. She explains that upon the arrival of white settlers to the area, tit-for-tat skirmishes ensued.

The Arapaho sought to support early white travelers by providing food and guidance with the stipulation that they not make permanent settlements. Many capitulated, then they found gold. Treaties were signed, the land was taken, new treaties were signed, and the battle for Colorado began.

Violence on both sides erupted. Volunteer cavalry men battled the Cheyenne dog soldiers in a fight for supremacy that would ultimately lead to the massacre, the expulsion of tribes from the Colorado territory and the path to secure statehood.

In the summer of 1864, Gov. John Evans met with the Cheyenne Chiefs Black Kettle and White Antelope along with an Arapaho delegation. The tribes were looking for peace and provisions after the military and white settlers decimated most of the buffalo herds that sustained them. Evans promised them safety, freedom to hunt and provisions if they stayed near Sand Creek.

Evans gave Black Kettle an American flag to hang above a white flag as a sign of peace. Under this plea, the tribal chiefs and their families camped.

Following the beginning of the Civil War the number of volunteer soldiers throughout the plains, including at the nearby Fort Lyon, increased. Some of these men held dreams of being elected to office and could claim political clout by fighting Native tribes.

“The military had a culture of shoot first and ask questions later,” Mason said.

The encampment held an estimated 750 Cheyenne and Arapaho, with very few warriors. The infamous Cheyenne dog soldiers, who had been responsible for most of the attacks on white settlers, were not present.

When Black Kettle and White Antelope heard the cavalry approaching they raised the two flags and walked to the edge of camp. When White Antelope realized that Chivington and his men arrived in violence, he kneeled and sang the Cheyenne death song, translated as, “Nothing lives long, only the earth and mountains.”

Against the peaceful encampment Chivington brought 675 troops and two Howitzer cannons. The cannons were fired into the camp while the cavalry set fires and killed. At the far end of camp mothers told their children to run up the dry creek bed. Holes were dug in the sand in search of refuge until cavalrymen used the cannons to shoot into the holes. The massacre lasted 9 hours with troops staying another day to mutilate bodies.

According to Mason, the well-worn path from war hero to political office was Chivington’s motivation. With the hopes of being elected to congress, he killed an estimated 230 people, well over half being women and children.

Chivington was welcomed to Denver as a war hero, while trophies from the massacre lay in display at the Capitol building. However, his political prospects soon fell flat with the beginning of a congressional investigation.

Capt. Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, two men under Chivington’s command, refused to participate in the massacre. The two wrote to congress recounting what they saw, triggering congressional and military investigations.

While the letters blackballed Chivington from politics, public sentiment did not entirely change towards the tribes. In January 1865, after testifying against Chivington at a military court of inquiry, Soule was killed in the streets of Denver.

Park Ranger Teri Jobe elaborated on the site’s correlation with modern-day police violence, “The things that were going on in the 1860s are very similar to the things that are going on today,” Jobe said. “There was a lot of fear, a lot of anger, a lot of misunderstanding between the white settlers and the Native tribes.”

This divergence in the understanding of history is also visible in the monument that stands atop the bluff near the creek. The red, gravestone shaped block reads “Sand Creek Battle Ground.” Kiowa County placed the memorial in 1950 before legislation passed to re-name the event as a massacre.

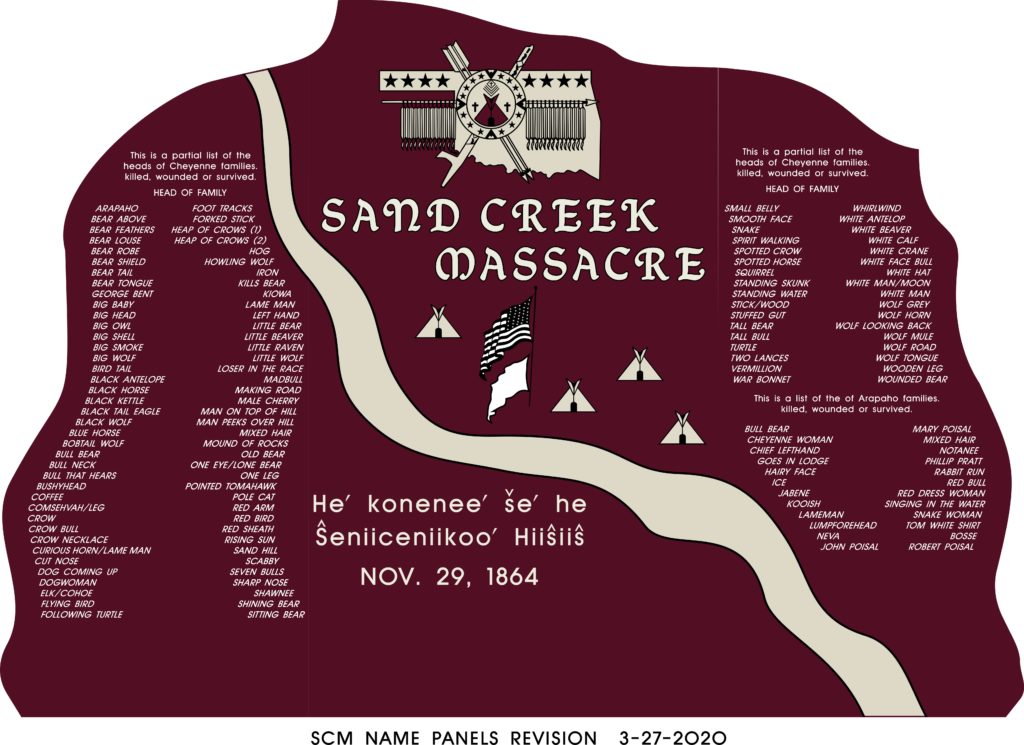

Fred Mosqueda’s most recent project is to better define the history of Sand Creek in the form of a new monument.

“You have to do tricks to get something done with the government,” Mosqueda said. “But they do listen to us, that’s why you hear the presentations being political. We believe if we don’t educate the people about it then they will never know the life that we lived.”

The monument will stand larger, with the names of all the heads of families present during the massacre. At the top is the seal of the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. In the center of the monument, an American flag sits above a white flag.

Collaborative Healing

Previously, this monument marked a meeting place for the Cheyenne and Arapaho’s annual Spiritual Healing Run. Since 1999, the tribes have communed on the bluff before beginning a nearly-200 mile relay-style run to the Colorado state capitol. The relay is timed for runners to arrive at the capitol on the anniversary of the massacre on Nov. 29.

Despite the tribes being split between Oklahoma and Montana, each year brings an impressive turnout. In 2019, 45 runners and 230 non-running tribal members came to the site wanting to share memories while healing for the future.

According to Mosqueda, the event serves many purposes. For non-tribal Colorado residents, it’s a reminder of a history long buried. For the tribe and its children, it provides a source of healing and a powerful education.

Before the run begins, Cheyenne and Arapaho children stand on the bluff while listening to the stories of the massacre and their ancestors.

“Each child that I’ve been with always tells me that they feel very, very sad. Some of them cry,” Mosqueda said. “They tell me, ‘I can feel the fear and the anguish and the sadness of what happened.’”

In a relay style, young people take turns running to the capital. Most of the children live in Oklahoma so not only must they run through the cold wind of a high plains winter, but they also battle a change in altitude.

“Our youngsters, they really come through when they run,” Mosqueda said. “It makes us really proud to watch them overcome.”

Upon reaching Denver, the runners stop at the site where Soule was murdered and kneel as a sign of respect. The runners then finish the race at the Capitol building where the tribes unite.

“We pray, we paint them, we show them how we cleanse ourselves, how we begin a new life,” Mosqueda said. “We take this anguish and this destruction off of you. Now you’re going to go out and live. Now you’re going to run. When you get to the Capitol you’re going to be cleaned.”

This desire for historical healing is felt by tribal members and non-tribal Coloradans alike.

Their daughter only recently finished kindergarten, but this is not her first experience with what her father calls “messy” history. Through the book series “Ordinary People Change the World,” Meyer and Yokley have worked with their daughter to process complex history with subjects such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Sacagawea, and Rosa Parks.

“You can see from what’s going on in the world that [the Sand Creek Massacre] is an important part of our history and an important part of preparing our nation for a better future,” Meyer said.

Their daughter only recently finished kindergarten, but this is not her first experience with what her father calls “messy” history. Through the book series “Ordinary People Change the World,” Meyer and Yokley have worked with their daughter to process complex history.

“For better or for worse, we started exposing her early to those conversations,” Meyer said. “Living in a predominantly white area of Colorado and Denver, it’s important to be aware of what else goes on in the world.”

Many parents are struggling with how to speak with their children about the big issues facing the country, whether it be COVID-19, police brutality or violent history. The NBC show “Nightly News Kids Edition” helps Meyer and Yokely communicate these big ideas with their daughter in conjunction with visits to historical sites such as Sand Creek and Wounded Knee.

“The circumstances of the last couple months pushed us to come down today,” Yokely said.

Before leaving the site, Eliza stood on the edge of the bluff looking at the creek below, seemingly unaware of the unrelenting heat. She fingered the traditional porcupine quill necklace her mother bought her at Wounded Knee.

State Sponsored Remembrance

The History Colorado Center is also thinking about how to make violent Colorado history more accessible to children and families. The museum is now working with the Cheyenne and Arapaho to develop an exhibit on the Sand Creek Massacre to open in July 2022.

The museum is a stark departure from its predecessor, the Colorado History Museum, in its accessibility to children. Throughout the History Colorado Center, children and adults can connect with history through games and interactive exhibits that feel reachable compared to museums of the past. Even painful history such as the Japanese Internment Camp at Amache is made accessible through an immersive barracks where recorded actors play the role of internees in explaining artifacts and their daily lives in the camp.

Shannon Voirol, the director of exhibits at the History Colorado Center, is working to find a way to make the Sand Creek Massacre exhibit available for children.

“For the Sand Creek exhibit, we’re working very closely with a group of tribal descendants, and we really are hoping it will have their voice and their hardships handling this story,” Voirol said. “It’s incredibly raw for them. They want you to ponder some pretty big things, which we need to.”

Voirol hopes to include some kind of signage outside the exhibit so adults can make an informed choice as to how they are going to speak with children.

Voirol and the tribes agree that an integral part of the exhibit will be talking about life before the massacre. While Colorado Social Studies Standards for schools require teaching about Native tribes, it is only required that they are taught in relation to clashes with settlers. There is no specific requirement mandating that children are taught about the massacre or that children learn about Native tribes before the arrival of white people.

“The tribe wants this to be an exhibit that shows that they had a rich, mature civilization before the massacre,” Voirol said.

The History Colorado Center currently tackles other complex histories throughout the museum. In their Colorado Stories exhibit, they show the Ku Klux Klan’s prominence in Denver in the 1920s, the protests of the Chicano Movement in the 1970s and the first mountain resort for Black Coloradans at Lincoln Hills.

While Ute history is discussed in the “Written on the Land” display, there is no full exhibit built around atrocities inflicted upon Native tribes. Voirol finds the unpacking of this painful history to be in the service of the populace she is charged with informing.

“We need to be students,” Voirol said. “We want an informed citizenry, in order to do that we must know where we’re coming from.”

The Next Generation

While the Cheyenne and Arapaho are working with various institutions to ensure their history is shared with all Coloradans, their focus is primarily on their children. Fred Mosqueda is making sure to educate the next generation in their own history and the broader story of violence in the United States. He draws the same connection between violence inflicted upon Black Americans by police and that upon his ancestors.

“Recent deaths have brought a light on how people are treated,” Mosqueda said. “It’s hard to change society when the beliefs are taught and deeply ingrained, but our children, as they come up and as they get educated, if they can bring this education to our people then we can teach them that they’re equal.”

While the protests following the death of George Floyd further ignited the tribal desire for equality, the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho will not participate in this year’s Spiritual Healing Run due to COVID-19.

However, Mosqueda is still planning on a tribal visit to the site in order to share its history. He sees the event as a chance to counter the negative messages the children receive from the world around them. He hopes that they know they are living descendants of people whose blood was spilled, but still live on through their progeny.

“They couldn’t get rid of you, you survived, you can carry on the teaching that the old people had from way back then. Be proud of who you are because they would want you to be proud. They lived a rough life, you live a rough life, you will survive because they did.”

It was a pleasure to meet you and talk. It was an interesting and informative piece. I appreciated hearing the stories of the tribal members and their reflection on the site.

I totally agree with JB. Thank you for writing this and making it available to each of us who reads it. You have provided a significant source of education for us.

Really interesting article with a lot of information I’m ashamed to say (as someone who’s lived in CO my whole life) I didn’t know before reading.