//Jason Wood, author of the blog Orthorexia Bites and memoir “Starving for Survival: One Man’s Journey With Orthorexia,” sits in the living room of his Denver home on March 12. Photos by Ali Mai | [email protected]

Before Denver resident Jason Wood was diagnosed with an eating disorder at age 34, he had a specific image in his mind when he pictured who could develop one. As a cisgender man, he didn’t fit the criteria.

“I didn’t even think I was battling an eating disorder because the stereotypes say that it doesn’t happen to me, that it doesn’t happen to adult men,” Wood said. “I think we also assume that eating disorders usually happen to just young, skinny, affluent females, and we disregard the fact that it can happen to anybody in any body size. It can happen to anybody of any sexuality, or of any social or of any income class, or anything like that.”

Wood struggled with disordered eating since he was young, eventually developing into orthorexia nervosa, an eating disorder defined by an unhealthy focus on healthy eating. Since orthorexia hasn’t been adopted into formal medical manuals, Wood’s doctor referred to his condition as an unspecified eating disorder.

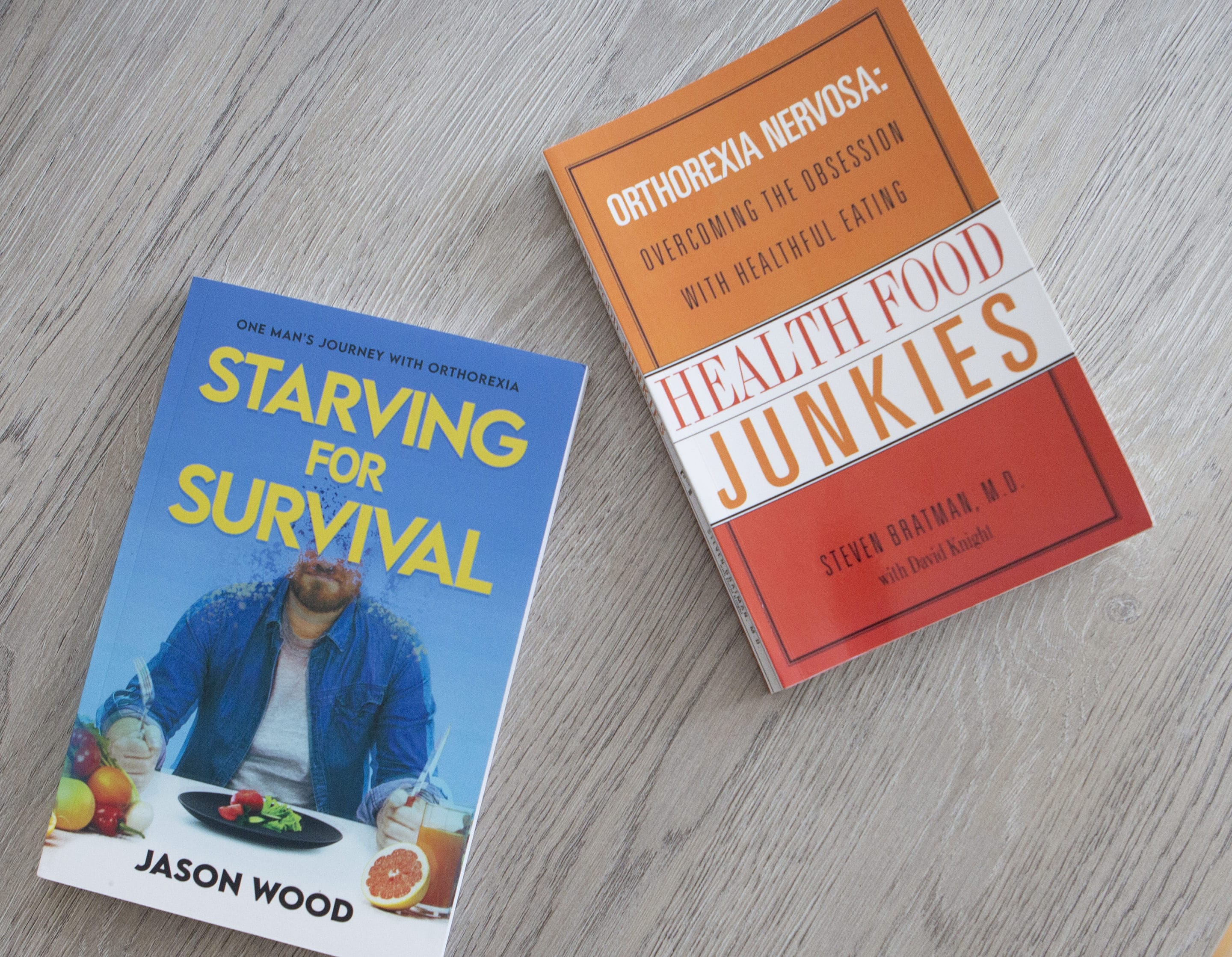

In Wood’s debut memoir released in January, “Starving for Survival: One Man’s Journey With Orthorexia,” he chronicles the early signs of disordered eating in his childhood and battle with a full-fledged eating disorder in his adulthood.

Despite early onset symptoms, no one around him, including himself, suspected it. Even after Wood was diagnosed in 2020, his recovery was set back. His doctor didn’t know who to send him to for his orthorexia symptoms and told him to look online for resources.

“I started looking for resources, but every time I found a website or a treatment center, it was these young females and women who were featured on these websites, and it made me think, ‘OK, well, this can happen to a guy,’ or ‘OK, well, that place won’t be able to do anything for me. They’ll just say that I need to go elsewhere to talk to someone else,’” Wood said, adding that the initial barrier led to about a month’s delay between receiving a diagnosis and actually meeting with a therapist.

Stereotypes reinforced through statistics

According to an estimate from the National Eating Disorder Association, 20 million women and 10 million men in America will have an eating disorder at some point in their lives.

Dr. Elizabeth Wassenaar serves as regional medical director at the Eating Recovery Center, or ERC, and Pathlight Behavioral Health for the mountain and West regions. She said she’s skeptical of current studies, and questions if they truly capture the full scope of the issue.

“I would say that in reality, we don’t know because we don’t have data to support how widespread eating disorders are in populations that are not typically represented or identified as having eating disorders,” Wassenaar said. She pointed out that, although most data is on young, white cisgender women, eating disorders affect everyone. She said that people outside the box of what is considered the norm for eating disorders are underrepresented in the data, which also has a narrow focus on anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

The lack of inclusive data can make it difficult for individuals and their loved ones to recognize an eating disorder. And if they do realize they need professional treatment, healthcare providers may minimize the severity of their case.

Navigating insurance is another barrier to treatment. Wassenaar said that insurance companies look at health markers such as BMI calculations, heart rate and lab work. But to be considered severe, a patient must go from “normal weight” to underweight. Patients that fail to meet this standard can struggle to gain funding support for treatment. Even recognizing a problem exists and jumping through hoops for insurance coverage is no guarantee of quality treatment.

“Even if they can get funding support, they might be put into a lower level of care, when in fact, the severity of their behaviors means that they really need a higher level of care; they need 24-hour care, but they don’t meet certain criteria so they’re put into outpatient care,” Wassenaar said.

Wassenaar said symptoms like excessively healthy eating, compulsive exercise or binge eating—which is recognized as different from bulimia when compensatory actions aren’t present—could be overlooked if the patient doesn’t meet set criteria.

Though it isn’t the only way the ERC defines the severity of a case, the center uses health data to inform treatment such as heart rate, blood pressure, weight change over time and lab data. Using overexercise as an example, the ERC uses health data to determine if someone needs medical observation. Someone who engages in a lot of exercise typically has a slower heart rate, which can cause a patient’s heart to stop while sleeping. Electrolytes can be abnormal from eating disorder behaviors, leading to cardiac arrest, she added.

The ERC also uses level of impairment as an indicator of how severe a patient’s case is. They consider how often someone engages with their eating disorder, how difficult it is to stop their behaviors and if their disorder disrupts their work and relationships.

If a patient has a less severe case of eating disorder but higher rates of suicidal ideation or a suicide plan, the ERC will place them in a higher level of care.

“Eating disorders, as a rule, never exist in isolation. Typically, people have anxiety disorders or mood disorders that co-occur and those anxiety and mood disorders can be very destabilized as well. So people with eating disorders struggle significantly with self-harm and with suicidality,” Wassenaar said.

Wassenaar said that anorexia and bulimia patients are the main clients who seek treatment from the ERC. However, they are seeing a shift toward more patients with binge eating disorder and unspecified feeding or eating disorder, or UFED.

Orthorexia: harm in the pursuit of health

Though formally Wood falls under the UFED category, his symptoms matched orthorexia.

Orthorexia takes “clean eating,” such as selecting organic produce or plant-based, keto and raw diets, to an extreme. It differentiates itself from eating disorders like anorexia in motivation. While anorexia nervosa is characterized by fear of gaining weight, orthorexia is driven by a need to be healthy while ironically harming the sufferer’s health.

The term was first coined in the late ‘90s by then Colorado physician Steven Bratman, M.D., but is yet to be adopted into psychiatric diagnostic tools such as the DSM-5, which was last updated in 2013.

Wood said he’s been on different parts of the spectrum of disordered eating. Disordered eating is a negative relationship with food while eating disorders are considered a mental health disorder and are often about more than just food and body image.

In high school, Wood joined Weight Watchers and began counting calories. He said he often overachieved by consuming less than the calorie goal set for him during the program. Wood considered his habits during that period as disordered eating.

At one point, Wood believes he met the criteria for anorexia nervosa, but after a Colorectal cancer scare at age 29, he turned to “clean eating.” Wood’s grief and anxieties from losing both his parents to cancer by the time he was a young adult, intensified his orthorexia behaviors.

He researched foods for their health risks and benefits and categorized them into bad and good. Wood pre-planned meals and felt deep anxiety around unplanned restaurant visits with friends. Hiding his eating disorder, he would spit the “bad” food into a napkin so his husband didn’t see.

Being categorized under UFED felt like checking the “other” box for Wood. Without a name, his eating disorder didn’t seem as serious.

Wood came across the term orthorexia for the first time while reading “Goodbye Ed, Hello Me: Recover from Your Eating Disorder and Fall in Love with Life” by Jenni Schaefer.

“It was three or four months after my diagnosis that I would finally hear the term orthorexia for the first time, and I was angry because, I was like, ‘How did I go so long listening to the stereotypes? How did I think that guys don’t develop eating disorders?’” Wood said.

From that moment, Wood decided to share his story so other people facing the same problem wouldn’t have to battle alone.

Strength in vulnerability

Before losing his father as a child, Wood was told that he was now the man of the house. Despite his father not pushing masculine stereotypes onto him, Wood still felt societal pressure to step into that role he saw men play in movies and what other kids said was manly: Be strong. Be tough. Be a man.

“I think about a time when I was stung by a bee on the second-grade playground, and my finger was swelling and the stinger was stuck in my finger. And rather than tell anybody, I kept it to myself because I didn’t want to be made fun of. I didn’t want to be the boy that was crying,” Wood said. Holding onto the pain of the stinger was the perfect analogy for the way he held onto pain as a teenager and young adult.

Pressure to be manly played into Wood’s eating disorder. He felt inadequate when he didn’t build up huge muscles from his frequent gym visits. He didn’t tell anyone that he was struggling.

But today, Wood sees embracing vulnerability as a better definition of masculinity.

In February 2021, Wood launched his first post on his blog called “Orthorexia Bites,” with the tagline “Men develop eating disorders, too. Trust me, I know a guy!” The logo is a sprinkled doughnut with a bite taken out of it, an homage to getting doughnuts with his parents and a food that Wood viewed as bad while battling his orthorexia.

Since starting his blog, Wood has gained a following of about 100 readers and frequently shares his journey at speaking events and as a guest on podcasts.

Social media can be triggering for people with eating disorders, with photos of influencers promoting fad diets, intermittent fasting and gym photos. Wood said there’s nothing wrong with pushing a healthy lifestyle but thinks it should come with boundaries. On his Instagram, which has nearly 2,000 followers, Wood said he shares his highlights and lowlights throughout his recovery journey. He added he refrains from posting weight loss numbers and before-and-after photos to be conscious of his audience.

His 2022 memoir included even more personal details that even his husband and friends weren’t aware of. Though it caused him anxiety, Wood says it’s worth it because “vulnerability breeds vulnerability.”

About a year ago, Pennsylvania resident Matt Billas was early into recovering from his eating disorder when he got connected to Wood through Billas’ wife’s author network.

After a couple of years of progressively losing weight, Billas was hospitalized for two days after having a seizure in 2020. It was a wake-up call for him, that he was subjecting his body to too much stress. He was diagnosed with body dysmorphia and anorexia, though he thinks orthorexia fits his experience better.

Billas fractured his leg running a race three years ago. His need to compensate for his lack of running by biking quickly turned into overexercising. Billas started showing orthorexia symptoms with his healthy eating habits.

“It all just hit a low the year leading up to my hospitalization. With the pandemic on top of it and anxiety with work and life and just feeling like I was losing control on all the other aspects of my life, I took what I could in the form of eating and exercise,” Billas said.

Billas said he remembers reading about celebrities battling eating disorders and always assumed it was an issue adolescent girls faced exclusively. Before his diagnosis, Billas researched eating disorders and could see some of his behaviors described. But no one suspected him of having a serious issue.

“Everything that you see about [eating disorders] portrayed in the media, and the news, or TV, is not even a fraction of what all is out there and there’s just no single definition of it that fits everybody. And I think that’s the problem I went through, thinking that there was and if I didn’t fall into it, it must be something else,” Billas said. “I must not be doing something wrong.” Having knowledge of the disorder would have also lessened the suffering for not just Billas but also his friends and family.

Through Wood’s monthly writing group and the “Starving for Survival” book launch, Billas has met others like him. He’s appreciated finding people he can relate to through recovery.

When Wood first started sharing his story, he attended peer support groups. Though he valued the connections he made, he didn’t find a community of men that understood his experience until he started his blog. They now have weekly check-ins to not just talk about their eating disorder, but to simply catch up on life.

“It’s so nice to know that you’re able to connect with somebody else who kind of shares the same perspective of the disorder and has faced kind of that same stigma and stereotypes that you have,” Wood said.

Healthy relationships are the antithesis of eating disorders, Dr. Wassenaar said. If you are concerned for someone in your life, she said, you can help by letting them know you care and want to support them.

The Eating Recovery Center offers free confidential assessments for those seeking help for themselves or someone they know. Centers can be searched by location here.

Enjoyed this story? Help us keep the lights on! Supporting local press ensures the stories you want to read keep coming, become a member for free today! Click here.

0 Comments